SEMIBEGUN 022: THROUGH THE CRATES AND AROUND THE CORNER

THE WACKY WORLD OF LIBRARY MUSIC

Air Date: January 14, 2024

What is library music? Viewed initially as background music for various forms of media primarily made in Europe from the 1960s to the 1980s, library music brought many session musicians together to make music they wouldn’t be able to otherwise, from schlocky conventional muzak to psychedelic drum-centric freakout jams. Over the years, library music has served as the source material for many hip-hop producers and has influenced some of the most prolific artists of the 21st Century. Guest curated by composer-filmmaker-researcher Orson Abram, this mix answers (and challenges) that question with an hour of music that blurs the lines between foreground and background, conventionality and abstraction, and musical intention through genre overlapping.

TRACKS

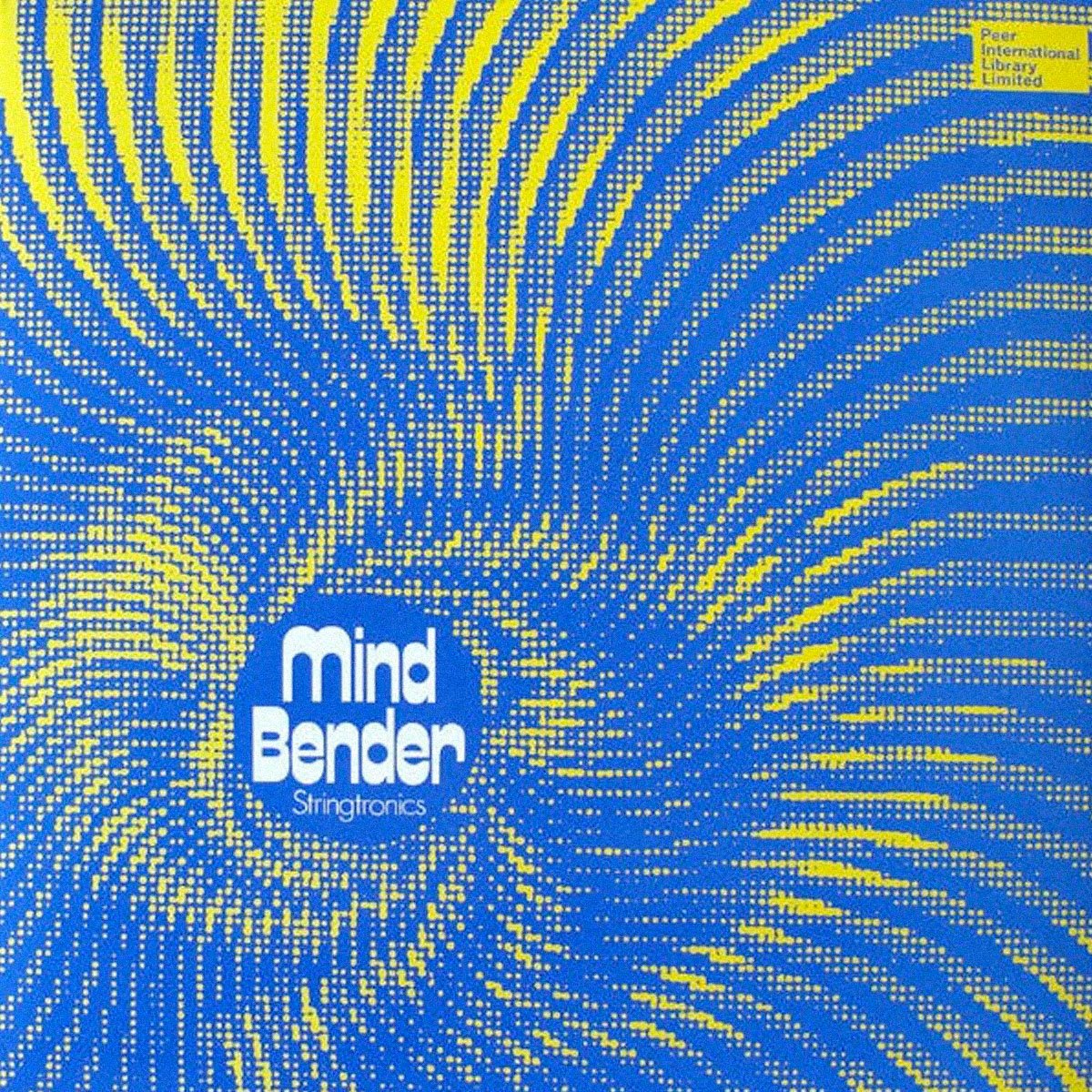

Barry Forgie/Stringtronics – “Dawn Mists”

Mindbender (1972); Peer International Library Limited, UKStelvio Cipriani – “Mary’s Theme”

Femina Ridens (1969); CAM, ItalyNino Nardini/Stringtronics – “Tropicola”

Mindbender (1972); Peer International Library Limited, UKBernard Fevre – “Pendulum”

The Strange World of Bernard Fevre (1977); L’Illustration Musicale, FranceSyd Dale – “Beguine for Trombone”

Gentle Sounds Volume 2 (1970); KPM Music, UKRichard Demaria – “Next Episode”

À Écouter (1974); Chappell, FranceBrian Bennett – “Solstice”

Voyage: A Journey Into Discoid Funk (1978); DJM Records, UKTrevor Bastow – “Videodisc”

The Video Age (1980); Bruton Music, UKBernard Estardy/La Formule Du Baron – “Monsieur Dutour”

La Formule Du Baron (1971); CBS, FrancePaul Piot et Son Orchestre – “Amour, Vacances Et Baroque”

Dance and Mood Music Volume 4 (1968); Chappell, FranceAlan Moorhouse – “Expo In Tokyo”

The Big Beat Volume 2 (1970); KPM Music, UKAlan Hawkshaw – “Beat Me ‘Til I’m Blue”

The Big Beat (1969); KPM Music, UKNino Nardini/The Machines – “Icebreaker”

Electronic Music (1973); Chappell, UK/FranceBernard Estardy/La Formule Du Baron – “Cha Tatch Ka”

La Formule Du Baron (1971); CBS, FranceAlan Parker/Madeline Bell – “That’s What Friends Are For”

The Voice of Soul (1976); Themes International Music, UK/USAMadeline Bell – “That’s What Friends Are For”

This Is One Girl (1976); Pye Records, UK/USAJean-Claude Petit – “Skyway”

Jean-Claude Petit (1974); Charles Talar Records, FranceArmand Frydman – “Jungle”

Fusion (1981); Sonimage, FranceBasil Kirchin – “Silicon Chip”

Silicon Chip (1979) [previously unreleased until 2017]; Trunk Records, UKJames Asher – “Oriental Workload”

Action Disco (1979), Studio G, UKTrevor Bastow – “Integration”

Hey Disco! (1979); Programme Music, UKJeroen Vink/Waka Wakah – “Waka Wakah”

Horns and Drums (1985), Reliant, NetherlandsKlaus Weiss Rhythm & Sounds – “Time Signals”

Time Signals (1978); Selected Sound, GermanyJack Arel, Pierre Dutour et Son Orchestre – “Top Rally”

Dance and Mood Music Volume 19 (1972); Chappell, FranceNino Nardini/New Sounds – “Catch That Man”

Chappell Mood Music Volume 16: New Sounds! (1967); Chappell, FranceJonny Trunk – “Zeus”

The Inside Outside (2004); Trunk Records, UKRobert Mellin & Gian Piero Reverberi – “Adrift”

The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1964), Silva Screen Records, USA/UK/ItalyRené Costy and his Orchestra – “Scrabble”

Chappell Mood Music Volume 26 CMM226 (1972); Chappell, BelgiumAdrian Baker & Roy Morgan – “In Close Harmony”

Voices in Harmony (1979); Bruton Music, UK

An Introduction to the Strange, Wacky, Complex World of Library Music

Orson Abram

What is Library music?

The common answer to this question, which has been on my mind for at least the past few years, is, simply, stock music. However, there is more to library music than just simply being stock music: Library music features none of the hypnotic, droll, manipulative elements present in Muzak or Mood music (although there is overlap within the genre labels themselves!). The popularization of library music coincided with the industry need to cheaply fill media, such as radio but more commonly TV and film, with background music––music that suited a variety of themes and could be made quickly and efficiently. What makes something Library music is not based on whether it fits within a certain genre; no particular musical characteristic defines library music besides a tendency towards largely forgettable instrumental works. Rather, Library music is characterized simply by its purpose and time and place of production: specifically, the music made between the 1960s and 1980s for commercial use in primarily Europe and occasionally the US.

Session musicians, already working on various commercial soundtracks at the time, came together on the side to make anonymous, background music quickly that showcased some level of technical proficiency without diverting the audience's attention from content of the media. In its heyday, Library music was huge for those in the European (especially British) media industry. Although never intended for public consumption, many library music labels formed throughout the European continent as it became an easy way to make music. And as music, it succeeded in its mission of replicating any mood/function whatsoever while remaining unobtrusively in the background. A few years ago, I re-watched Patrick McGoohan’s 1967 British Sci-Fi Miniseries Masterpiece The Prisoner, and I was struck by how effective the incidental music in the show truly is, contributing to a mood but never overtaking the action (most of which is music from library labels such as Chappell). One of the tracks in this mix, Nino Nardini’s Catch That Man, can be heard in this final scene from an episode of The Prisoner, nailing the humorous mood of the rest of the episode. The best Library music is musically interesting while simultaneously being mundane enough to function as background music.

However, during the 1970s, various musicians within the Library music community used these quick, easy gigs as means to experiment with various instrumentations, musical motivic structures, and especially synthesizer presets. As a result, the library music at this time started to shift into the strange disposition of being too strange and wacky to exist as conventional background music but too subdued (and instrumental) to hit the mainstream. Artists such as Nino Nardini, Anthony Bell, Bernard Fevre, and Bernard Estardy paved the way for many experimental synthesizer-based artists in the future years (with Fevre releasing music under the now-semi-famous electronic-disco-oriented Black Devil Disco Club moniker into the 80s). Additionally, many pieces of library music (such as Rene Costy’s Scrabble which was sampled in J Dilla’s 2001 Fuck the Police) sought a resurgence in the 1990s/2000s when hip-hop producers began sampling the catalog. Artists such as Luke Vibert/Wagon Christ and Jonny Trunk (both of whom are also extreme library music collectors and experts on the history of the genre, the latter of whom released the literary ode to Library music entitled “The Music Library”) use primarily Library music as sample materials. Because of this, there has been a meteoric rise of Library music collectors and interest in these often super-rare records.

Not all Library music is interesting however. A lot of it is bland, uninteresting, predictable, and is some of the most awful music you’ve ever heard. As Jerry Dammers of the famed ska band The Specials writes in the Foreword to Jonny Trunk’s 2005 encyclopedic library music book “The Music Library,”

Don’t ever let anyone sell you a library record until you’ve heard it. As any library crate digger will confirm, a large proportion of the vast amount of library music made is the most indescribable dreck, and would break the mind of even the most warped library freak.

That being said, this mix does not feature that demographic of Library music. I have carefully chosen almost all of my favorite Library music pieces for this mix.** Many of these songs have stuck with me for years after first hearing, and some of them blur the lines of defining themselves as library music. For example, Stelvio Cipriani’s luscious, beautiful Mary’s Theme is from the soundtrack of Piero Schivazappa’s 1969 erotic-thriller Femina Ridens (The Laughing Woman), but since Cipriani’s music consists of both library and soundtrack music (almost interchangeably), I included his music here. Also featured in this mix are two contrasting versions of Madeline Bell’s optimistic, groovy, and fun That’s What Friends Are For, one of which was recorded for the Themes library with Alan Parker, and the other off of her solo album. Another outlier of not necessarily being traditional library music is Jonny Trunk’s Zeus, from his nu-library music album The Inside Outside, which samples a piece from the Adventures of Robinson Crusoe TV series soundtrack, which immediately follows on the mix.

The line of what is/isn’t Library music is very thin, and the crossing of these boundaries are perhaps what makes the genre very unique and special; it seems as if even the musicians/composers involved broke these vague rules, and this makes for the most special music. In many ways, Library music paved the way for not only future stock music, but much more; from hip-hop to contemporary synthesizer music (such as Belbury Poly and The Advisor Circle) to cinema (the soundtrack to 2009 blaxploitation comedy Black Dynamite is composed completely of library music, and one of the tracks on this mix, Basil Kirchin’s tech-disco song Silicon Chip was used as the credits music for the 2023 horror movie M3GAN), Library music’s resurgence in popularity and subsequent influence is powerful, and although the genre can’t truly be defined, its impact on music culture is heard and felt in a very significant way.

** due to time constraints three noteworthy tracks where not included but are well worth experiencing: Mermaid by Alan Hawkshaw and Brian Bennett, Way Star by Rubba, and Drug Song by Janko Nilovic)

About Orson

Orson Abram (they/he) is a composer, percussionist, improviser, filmmaker, and sound artist originally from Columbus, Ohio. They currently attend Oberlin Conservatory and College, where they study TIMARA (Technology in Music and Related Arts) and Cinema Studies under the instruction of Francis Wilson, Rian Brown-Orso, Ross Karre, and Pat Day. Orson's work deals with personal memory and its translation into various multimedia forms of art, from video art, performance art, and installations to notated music and improvisation. Their work has been featured at festivals such as Darmstadt Ferienkurse, So Percussion Summer Institute, Summer Institute for Contemporary Performance Practice (SICPP), and NYCEMF. Check out their work on SoundCloud, YouTube, and MixCloud.