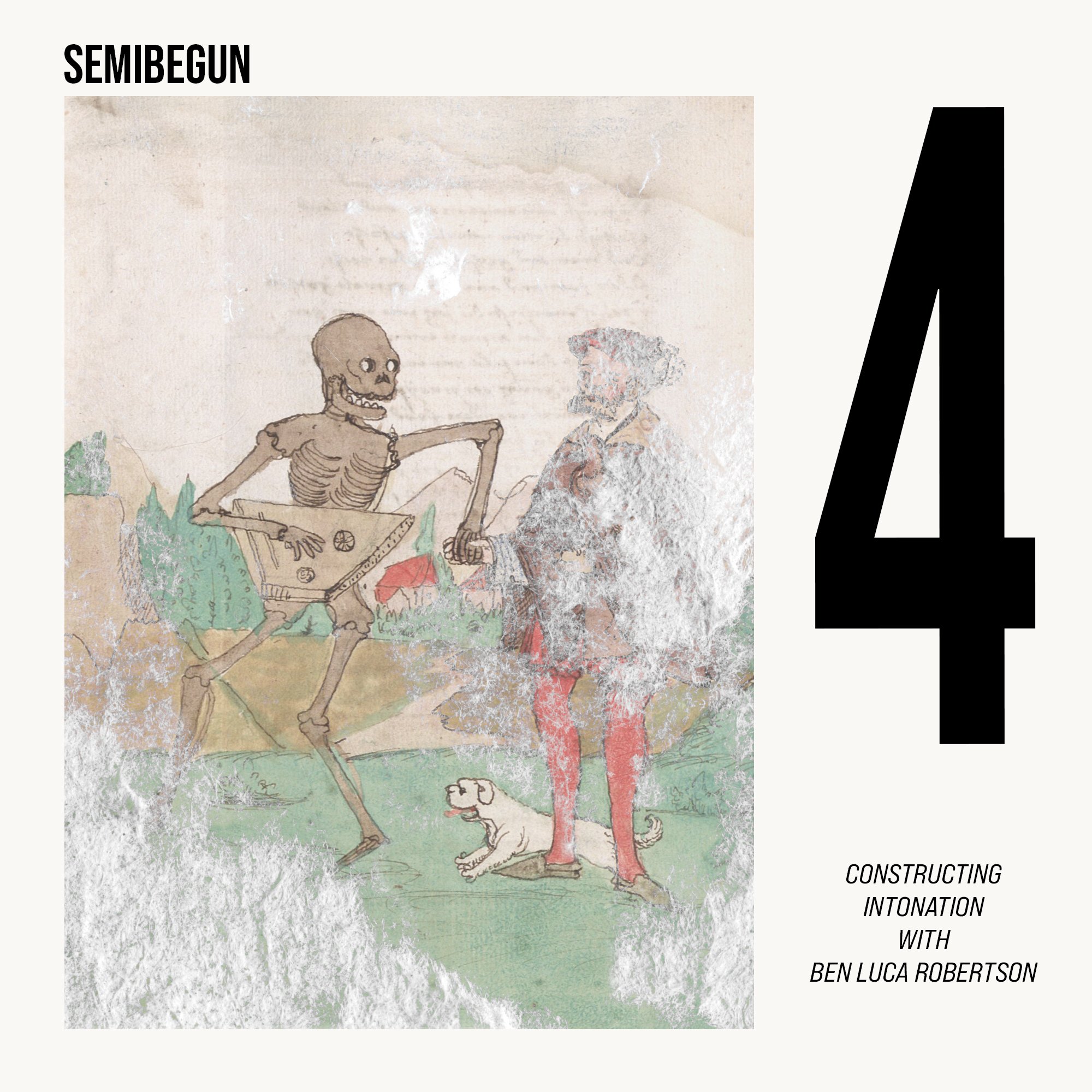

SEMIBEGUN 004: CONSTRUCTING INTONATION WITH BEN LUCA ROBERTSON

Air Date: July 20, 2022

Featuring Semibegun's first guest, composer and instrument designer Ben Luca Robertson, this mix presents an approach to microtonality informed by the guitar tuning experiments of post-punk and no-wave while situated within a history of intonation theory that stretches back to antiquity. Hear Ben's music and instruments alongside Siouxsie and the Banshees, Joy Division, Sonic Youth, James Tenney, Harry Partch, This Heat, Glenn Branca, and Cocteau Twins. Read the conversation with Ben below to learn more about his thoughts on composition, just intonation, actuated string instruments, punk rock scordatura, Pythagoras, ancient greek flute hole aesthetics, and anything that isn't twelve tone equal temperament.

TRACKS

Ben Luca Robertson – Artemisia #34-53

Joy Division – Exercise One

Sonic Youth – Death To Our Friends

Siouxsie And The Banshees – Hybrid

Glenn Branca – Symphony No. 3 “Gloria,” Second Movement

James Tenney – Critical Band

Dancing for the Flesh (Ben Luca Robertson) – Thamnophis sirtalis

Harry Partch – Barstow – Eight Hitchhiker Inscriptions from a Highway Railing at Barstow, California

This Heat – 24 Track Loop

Cocteau Twins – Blind Dumb Deaf

Siouxsie And The Banshees – Israel

Ben Luca Robertson – Artemisia #54-83

ABOUT BEN

Born in 1980, Ben Luca Robertson is a composer, experimental luthier, educator, and co-founder of the independent record label, Aphonia Recordings. From growing up in the American Pacific Northwest, impressions of pine trees, channel scablands, volcanic outcroppings, and relics of boomtown decay bear a haunting influence upon his music and outlook. His compositions reflect an interest in autonomous processes, landscape, and biological systems—often supplanting narrative structure with an emphasis on the physicality of sound, spectral tuning structures, and microtonality. In the past, Ben has worked with regional biologists to sonify data from migrating salmon and composed music based upon taxonomic classification and geographic distribution of rare snake species’. Beyond the natural world, the droning hum of high-tension wires, lilting whistles from passing freight trains, and small-town punk rock hold equal sway in this sonic landscape. Ben’s current practice focuses upon the intersection between actuated string instrument design and just intonation. By definition, these actuated instruments utilize electronic transducers, such as electro-magnets, to induce ghostly vibrations in strings. To realize his compositions, Ben constructs bespoke instruments and scales—at times pairing these new instruments and extended tuning techniques with traditional chamber ensembles. His latest piece, Artemisia, features performances by viola da gamba consort, Science Ficta, as well as a pair of newly-conceived actuated instruments: Rosebud I and II.

FOUNDATIONS

JUST INTONATION

(Per Harry Partch from Genesis of a Music) “A system in which interval and scale building is based on the criterion of the ear and consequently a system and procedure limited to small (whole)-number ratios.” Therein, each ratio represents the fractional proportion between two frequencies. For example, the interval between the frequencies 550 and 440 Hertz can be represented as the just ratio, 5/4.

EQUAL TEMPERAMENT

A system of tuning and scale construction in which the octave is divided into a set number of equal intervals. The familiar, twelve-note chromatic scale is one example of equal temperament, wherein the octave is divided into twelve equal intervals (or semitones).

SPECTRAL MUSIC

An approach to sound spectra, acoustic properties of sound, as compositional material. Composers with spectral features in their work include Tristan Murail, Gérard Grisey, Horațiu Rădulescu, and James Tenney. For a far more thorough and less reductionist introduction to spectralism, please read Joshua Fineberg's article "Spectral Music."

INTERVIEW

HEATHER MEASE: As a composer and instrument builder who focuses on tuning as material for composition and design, what was your particular entry point into the world of just intonation?

BEN LUCA ROBERTSON: Well, my introduction to just intonation was a bit circuitous. I never followed a particular teacher or “school” of thought. Instead, I suppose that I’ve always sought out extended tuning practices as a means to an end—a way of accessing sonorities that are beyond the reach of traditional harmony. Really, my first conscious exposure to microtonal music came by way of post-punk and no-wave—particularly, early Sonic Youth records like Bad Moon Rising & EVOL. From either records sleeves or some anecdotal / pre-internet source, I somehow figured out that they were tuning their guitars in weird and unconventional ways. Not necessarily just intonation; but certainly microtonal. You know, open tunings where you might have four consecutive strings tuned to ‘D’—however some of those ‘D’s’ were either sharpened or flattened slightly. Listening back in retrospect, these narrow intervals often mirror the just ‘commas’ and other intervallic features Harry Partch describes in Genesis of a Music or those carefully notated pitches in pieces, like James Tenney’s Critical Band. As a teenager, this stuff blew my mind! These bands were creating sonorities every bit as strange & otherworldly as those generated by a synthesizer—simply by re-tuning their guitars! Sort of like Punk rock scordatura!

Of course, Sonic Youth led me to Glenn Branca—and Symphony No. 3 (Music for the first 127 Intervals of the Harmonic Series) was my first introduction to tuning systems derived from spectral content. This kind of physical logic really appeals to me and—as far as I’m concerned—just intonation is just one facet of spectral tuning. Mind you, at this point I didn’t know that spectral music was a thing. Honestly, I didn’t hear or read about French spectralists like Grisey or Murail until years later.

Anyway, going back to post-punk, I also heard microtonality as a byproduct of certain effects processing. Take Steve Severin’s bass tone with Siouxsie & the Banshees or The Glove. That deeply detuned, goth-rock chorus effect on tracks like Israel or Like an Animal introduces a parallel stream of narrow—dare I say, comma-like!—intervals on top of the bass melody. Intentionally just? Probably not. But certainly outside equal temperament.

HM: Your own instruments, particularly Rosebud which is used alongside Viol consort in Artemisia, have a vaguely guitar-like appearance with multiple strings and pick-ups. A layman could point out similarities to something like pedal steel. An actuated stringed instrument could potentially take many forms, but do you think this is another influence of post-punk?

BLR: Absolutely! Both familiarity with this music and what six vibrating strings paired to a humbucker pickup can do definitely factored into that. In addition to being the primary means of amplification, (the sound of) guitars and guitar pickups are also the timbral world I grew up with—whether that’s post-punk or country-western music. It’s familiar territory and it’s close to my heart.

HM: When you create a new instrument, compose for it, and perform with it, do you feel you’re operating within already established territories, for instance in the extended universe of post-punk and no-wave, or do you find yourself in territory that you yourself must define?

BLR: No one’s an island, right? However, without trying to sound too iconoclastic, I’m a lot less interested in cultural reference than I am sound or other physical systems. Whether it’s punk rock or art music, I’m really most comfortable operating in the periphery of any established scene or movement. That said, practical knowledge from other instrument-makers—particularly folks working with actuated instruments—has been essential to my practice. For example, there’s more than a hint of Nicolas Collins’ ‘Backwards Guitar’ in the construction of my instrument ‘Rosebud I’--you know, aluminum frame construction and electric guitar pickups for amplification and sound processing. Likewise, I installed the same electro-magnets as those used in Andrew McPherson and Edgar Berdahl’s actuated pianos. Practically-speaking, following these design specifications allowed me to resonate strings using manageable amounts of electrical current. You know, these past approaches just work and I’m happy to stand on the shoulders of giants!

In regards to theory & performance, I do lean heavily upon principles best codified by Harry Partch. The connections between Otonality, Utonality, and the harmonic/sub-harmonic series are concise and irrefutable in the way he presents them. In fact, it’s a shame Partch isn’t included in most music theory pedagogies! More specifically though, I find a lot of parallels between my approach to composition and Partch’s conception of ’Tonal Flux’—basically, the idea of connecting two, stable sonorities by way of extremely narrow intervals—or ‘commas.’ I mentioned those earlier in reference to Sonic Youth and Souxsie and the Banshees. Both groups seem to hint at that sound, through either re-tuning or effects processing. However, unlike Partch, I tend to treat commas as free-standing elements, as opposed to something which pivots between two states. I think of commas as more integral to my compositions.

Going back to spectra, I often steer that intervallic range and structure of my music around pyscho-acoustic principles—specifically, quantitative assessments of perceptual consonance and dissonance, or what some researchers term ‘roughness’. Particularly, I’ve taken a lot of influence from researcher Pantelis Vassilakis’ modeling of spectral roughness. As part of my live rig, I’ve implemented his algorithms in programming environments like Max/MSP and Pure Data. During a performance, these algorithms modify the balance of synthesized harmonics. Think of it like a thermostat, with a defined roughness value as the temperature setting. The same way a thermostat turns the heat up or down to match a certain temperature, my algorithm changes the balance of harmonics to match a defined roughness threshold. Essentially, I treat roughness as just another musical parameter to be performed.

Anyway, these are all generally pragmatic; as opposed to cultural or aesthetic influences.

HM: One of the things that strikes me most about Harry Partch’s music, besides being theoretically rich, is the significance of culture and mythology, whether Ancient Greek or Californian, in both his compositions and instrument designs. Thinking of pieces like Castor and Pollux and Barstow - Eight Hitchhiker Inscriptions from a Highway Railing at Barstow, California or instruments like his Kitharas. The Greek elements relate to tuning, construction, and content, so in this way the extra-musical influences in his work become tangibly musical. It goes way beyond surface level. I’m curious what, if any, comparable influences might be found in your own work?

BLR: This is an area where Partch and I may differ. I have an inkling that if he were alive to hear my music, he may not like it! Partch was really concerned with corporeality and creating pieces that involve theatre, where the performance requires acting out both its musical contents and cultural references. While I think his views on corporeality in performance are fascinating, they don’t necessarily touch on what I do. My concern is generally less rooted in culture than it is in sound itself. In this regard, our views diverge quite drastically. In fact, in some of his writings, Partch is more than a bit incredulous regarding the role of spectra in just intonation. Instead, his interests in sound and tuning manifest in modeling facets of the human voice. Again, our concerns are quite different here.

When I do reference extra-musical materials, I tend to orient towards biological processes, landscape, and other autonomous systems. This is where sonification comes into play–converting things like scientific data into sound or musical parameters. Hence, my collaboration with biologists to sonify the migration of Chinook Salmon. When sound can both reflect and serve the natural environment, all the better. That’s corporeal enough for me!

HM: In your own writing you primarily reference theorists of the twentieth century onwards like Partch, James Tenney, and Ben Johnston. There’s also so much early music and theory from antiquity, Pythagorean tuning perhaps most notably, that engages with various tuning systems. The ubiquity of twelve-tone equal temperament in western classical music is a more recent development than some might think. Do you see the treatises on tuning from antiquity as something completely other from the current space you’re working in?

BLR: No. Not at all. Like Pythagoras, Ptolemy, or Aristoxenus, I’m also engaged with empirical research—or at the very least, seek a physical logic for constructing sound and interval. Of course, their understanding of the physical world—specifically, sound and psychoacoustics—was limited by other factors; be they scientific or cultural.

In some ways, I think musicologist Kathleen Schlesinger provides the most concise bridge between tuning practices in Antiquity, Partch’s theories, and the physicality of instrument design. Her analysis of the physical proportions of the Aulos (an early reed instrument) frames Greek modal scales firmly within just intonation. While her work precedes Partch by decades, there are numerous parallels between them as researchers, if not practitioners. Like Partch’s conception of Utonality, Schlesinger classifies the seven Greek modes based upon intervals between the first thirteen sub-harmonics—or undertones. Both Schlesinger and Partch also emphasize an integral relationship between tuning and instrument design. However, instead of the divided string—or ‘monochord’, Schlesinger predicates historical tuning practices upon equally-spaced placement of holes on reed flutes. With her work, there is also a physical logic which I find really engaging.

HM: By working with viola da gamba ensemble Science Ficta on Artemisia, you have some experience with composing for period instruments and musicians with backgrounds in historically informed performance practice. From that experience, how do you perceive the tuning approaches of early music versus those of modern and contemporary music? Do you feel there is kinship between what you do with actuated stringed instruments and what a viola da gamba player does?

BLR: Yes! There’s definitely a kinship between these two practices. That’s what made it so great to write for this ensemble. In each case, physical design and proportionality are linked to tuning structure. In the case of the Viola da Gamba, moveable frets enable flexible tuning. With my own instruments like Rosebud II, moveable bridges and multiple courses of string allow similar flexibility. Again, I think about instrument design as a means to manifest specific tuning structures. This pre-compositional process often occurs in advance of constructing (or modifying) the actual instruments.

Of course, the main difference between the two practices (the viola da gamba player and my own) is the mode of physical activation: while the viol player’s bow initiates vibration of the strings, my actuated instruments rely upon electronic transducers, such as vibrating bridges or electro-magnets, to induce sympathetic vibrations from the strings. That said, both are physically embodied performances involving the periodic movement of sounding bodies, specifically strings.

When I composed Artemisia for Viol consort and actuated instruments, I put a lot of thought into the relationship between performed and actuated frequency content—essentially notating common just intervals between harmonics shared by each instrument. Without getting too technical, the viol provides the signal which drives the transducer, which brings the actuated instrument’s strings into sympathetic vibration. When performed notes from the viol coincide with harmonics generated by the strings of the actuated instrument, sympathetic resonance occurs. Like a ventriloquist and dummy, the viol is speaking through the actuated instrument—viol as ventriloquist; the actuated instrument as the dummy.

HM: My final question to you. What is on the horizon for your practice? Is there a specific piece to be composed, an imagined instrument to be built?

BLR: To be honest, I still feel like I’m learning to play these instruments. For instance, In the later stages of composing Artemisia, I began experimenting with preparation. The same way Cage would prepare the inside of a piano, I prepared the strings of these actuated instruments using strips of foil, straws, and other objects. Consequently, there’s a secondary level of interaction that’s happening between the actuated instrument’s performer, the signal that’s being used to resonate the strings, and these other physical interventions that affect timbre. In some cases, the act of preparation even imitates other instrumental techniques. For example, when I bring a string into a sustained resonance and press a straw down onto the vibrating surface, I end up producing a rapid ricochet effect similar to a ‘buzz roll’ (on a drum). Thus, through experimentation, I came upon a technique for introducing percussive elements into a practice more or less rooted in sustained drones. To sum it all up: I created tuning structures, instruments which enable those tuning structures, and now I’m learning how to actually play these instruments and understand what these interactions can afford.

HM: The discovery and exploration of your performance practice is an interesting point. When you create a new instrument you must also invent a performance practice. It’s a form of early music—it allows exploration, experimentation, and potentially leads to some amount of codification. You’re certainly past the primordial ooze stage, but there’s still so much more ground left to cover. I think this says a lot to your ability as an instrument designer, that they have the flexibility to grow with you as a composer and you the flexibility to grow with them.

BLR: The funny thing about creating new instruments is that there’s no one there to teach you to play them! You know, it’s not like I can take lessons.

June 23, 2022